It has long been known that a lens, however perfect, has limited resolving power.

As Lord Rayleigh pointed out in his seminal 1891 paper “On Pin-hole Photography,” diffraction imposes an inflexible limit on the resolution of any optical system. As a result, in such fields as microscopy, astronomy, and medical imaging, it is often challenging to discern cellular structures, far-away galaxies, or incipient tumours from the available data. Super-resolution aims to meet precisely that challenge—to uncover fine-scale structure from coarse-scale measurements. This problem also arises in electronic imaging, where photon shot noise constrains the minimum possible pixel size, and in many other applications, including signal processing, spectroscopy, radar, and seismology.

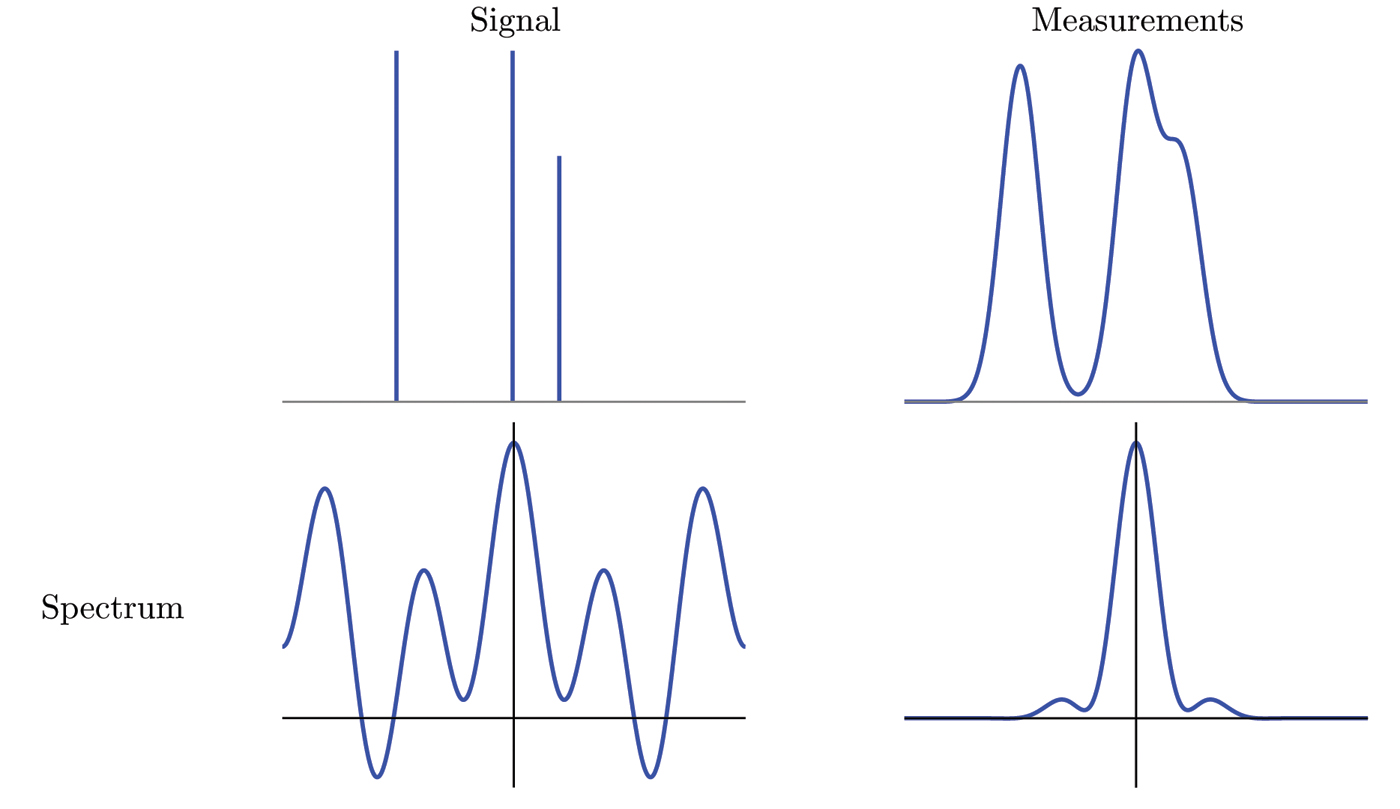

In its most general formulation, the problem of super-resolution is ill posed. This becomes apparent in the frequency domain. Low-resolution measurements essentially erase the high end of the spectrum; consequently, we cannot hope to retrieve the missing fine-scale information without prior knowledge of our object of interest. Under one popular assumption, we can model the signal as a superposition of point sources or spikes, which might represent celestial bodies in astronomy, molecules in fluorescence microscopy, or line spectra in signal processing. Figure 1 illustrates the resulting inverse problem: The aim is to estimate the train of spikes at the upper left from the blurry measurements at the upper right or, equivalently, to extrapolate the high frequencies at the lower left from the truncated spectrum at the lower right. Under what conditions can we hope to achieve this? The answer must surely involve exploiting the sparsity of the signal, which suggests connections with compressed sensing.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the super-resolution problem. Left, a highly resolved signal and its spectrum. Right, low-pass measurements of the signal and the corresponding truncated spectrum.

|

In a nutshell, compressed sensing allows the recovery of a low-dimensional structure embedded in a high-dimensional space. Surprisingly, this is achieved by taking non-adaptive randomized measurements and solving a tractable convex program. When applied to our model of interest, compressed-sensing theory guarantees that we can reconstruct any sequence of \(k\) spikes from approximately \(Ck\) random Fourier coefficients by solving the \(\ell_1\)-norm minimization problem

\[\min_{x}||x||_{\ell_{1}} \] among all signals \(x\) consistent with the data. Moreover, the recovery scheme can be stable in the presence of noise. This is possible because the random-sensing operator is well conditioned when its domain is restricted to the class of sparse signals. Intuitively, such a condition is necessary for recovery by any method in a realistic setting; otherwise, the signal could be completely lost in the measurement process.

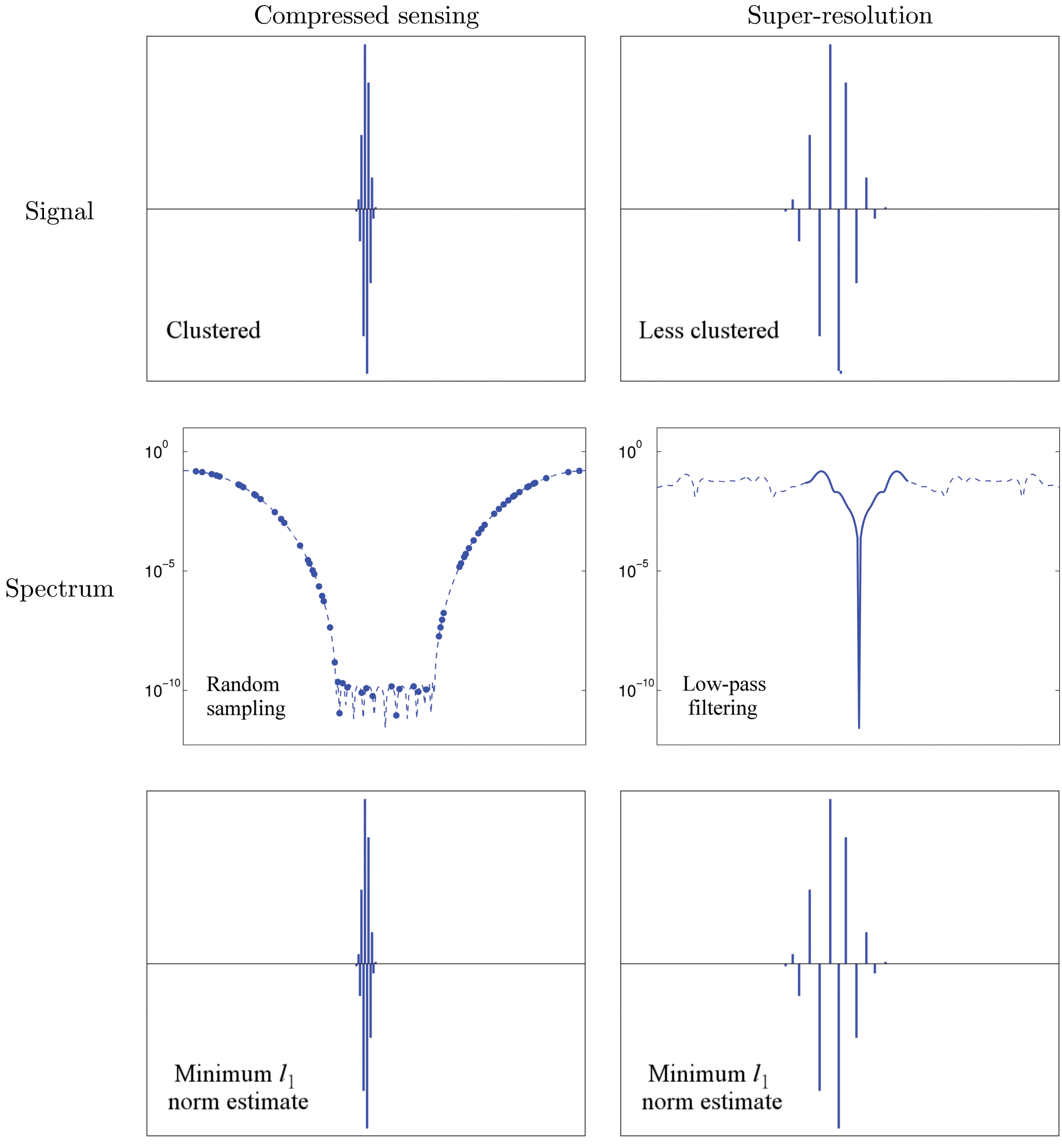

Returning to the problem of super-resolution: As a first step, we should investigate whether the low-pass operator is well conditioned when acting on sparse signals. This does not follow at all from compressed-sensing theory, which ensures that it is possible to interpolate the spectrum of a sparse signal from random samples, but says nothing about extrapolating the higher end of the spectrum from low-frequency samples. The second row of Figure 2 illustrates the difference between the two measurement schemes: In both cases we subsample in the frequency domain, but compressed sensing gives us access to the entire spectrum, whereas in super-resolution we are restricted to the low-pass frequencies. It turns out that low-pass filtering of sparse signals, unlike randomized spectral sampling, can be very badly conditioned. A simple example helps make this important point. The signal in the left column of Figure 2 is very sparse, but the fraction of its energy located in the lower quarter of its spectrum is only about \(10^{–8}\)! No recovery scheme—no matter how sophisticated—could possibly estimate this signal from low-pass measurements in the presence of even the slightest perturbation. In sharp contrast, if the whole spectrum is sampled at random, the measurements do capture a sizable fraction of the energy of the signal. Indeed, compressed sensing recovers the highly clustered signal from a quarter of its discrete spectrum, as shown at the lower left in Figure 2.

A careful reader might wonder whether the example on the left of Figure 2 is pathological, in the sense that the spectrum of most sparse signals might not be as concentrated in the high frequencies. We can do a simple experiment to test whether this is so. Consider the vectors of length 5000 that end in 4950 zeros. This defines a vector space of dimension 50 composed entirely of very sparse signals, to which we apply a low-pass filter retaining a quarter of the spectrum. Taking the singular value decomposition of the filter restricted to this vector space reveals that a subspace \(S\) of dimension 22 is almost completely destroyed; the fraction of the remaining energy for any signal in \(S\) is at most \(10^{–10}\)! This phenomenon was characterized theoretically by Slepian in the 1970s. His work on prolate spheroidal sequences confirms that, asymptotically, most tightly clustered sparse signals are almost completely annihilated by low-pass filtering.

Figure 2. Compressed sensing recovers any sparse signal, even highly clustered ones, from random spectral samples. Super-resolution via \(\ell_1\)-norm minimization extrapolates the high frequencies of sparse signals that are not too clustered.

|

Does this mean that super-resolution of sparse signals is completely hopeless? Not if we are willing to add some further structure to our model. We must impose conditions on the support of the signal to preclude its being too clustered. The right column of Figure 2 shows a signal that is identical to the one in the left column, except that its support is more spread out. Spacing out the spikes results in a spectrum that is not as concentrated in the higher frequencies. For such signals super-resolution from low-pass measurements is no longer hopeless. In fact, as shown at the lower right in the figure, \(\ell_1\)-norm minimization succeeds in reconstructing the signal exactly from the lower quarter of its spectrum.

The outcome of this example is encouraging, but is it typical? The answer is yes. Recent work has established that \(\ell_{1}\)-norm minimization super-resolves any train of spikes as long as the separation between spikes is at least \(2/f_c\), where \(f_c\) denotes the cut-off frequency of the measurements. Exact recovery is guaranteed even in a gridless setting, where the spikes may be supported at arbitrary points of a continuous interval. In that case, the recovery algorithm can be recast as a discrete semidefinite program, which locates the support of the signal with infinite precision. Furthermore, the method is provably robust to perturbations and can be adapted to signals of other types, such as piecewise-smooth functions.

To recapitulate, sparsity is not enough to characterize the problem of super-resolution. Refining the signal model to exclude highly clustered signals not only ensures that the problem is well posed in principle, it is actually sufficient to guarantee the success of a tractable method based on convex optimization. This illustrates a central theme in modern signal processing: Understanding the interaction between the sensing process and certain low-dimensional structures—such as sparse vectors or low-rank matrices—allows us to develop non-parametric algorithms that are remarkably successful at extracting information from high-dimensional data.

Acknowledgments: The author is grateful to Gilbert Strang for encouraging him to write this article and to his adviser, Emmanuel Candès, for his support.

Related Publication: E.J. Candès and C. Fernandez-Granda, Towards a mathematical theory of super-resolution. Comm. Pure Appl. Math., to appear.

Carlos Fernandez-Granda is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Electrical Engineering at Stanford University.